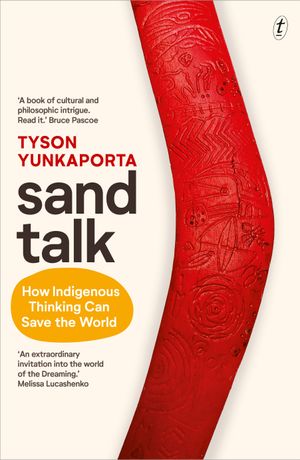

Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World

by Tyson Yunkaporta

read in Aug 2021

book info on goodreads

Having spent now more than four years in Australia, “Sand Talk” was an interesting read for me as it was the first more or less academic book that I read about Aboriginal culture. Surprisingly, many of the general themes of Aboriginal culture resonate with my thinking with regards to process, time and relationships. While the book covers many of these more general themes, it is primarily concerned with Aboriginal knowledge and how that knowledge could help the world become more sustainable.

The basic assumptions of what could be called an Aboriginal “ontology” as described by Yunkaporta come very close to a process-relational ontology. The First aboriginal law states that creation is an ongoing process and nothing is created or destroyed as a final state because of the complex relationships between systems. It is however relatively human-centred because it also states that humans are the custodial species of the world.

“Creation is not an event in the distant past, but something that is continually unfolding and needs custodians to keep co-creating it by linking the two worlds together via metaphors in cultural practice.”

This does not mean that humans are somehow superior or rulers. Instead humans must move with this process of creation and cannot necessarily shape its flow.

The Aboriginal understanding of time as non-linear is also in line with a process perspective. Interestingly Yunkaporta brings to our attention that in the English language we do not really have a word for non-linear except from the negative. That is because it is unintuitive to consider traveling, thinking, talking and time itself as anything but non-linear. Time for indigenous Australian moves in cycles such as the seasonal cycles of the landscape or the stellar cycles of the starry firmament. Furthermore, time cannot be separated from space. Time and space are usually the same word in Aboriginal languages.

Most of “Sand Talk” focuses on Aboriginal knowledge and knowledge processes. Aboriginal cultural knowledge develops in deep relationships and long processes.

“People today will mostly focus on the points of connection, the nodes of interest like stars in the sky. but the real understanding comes in the spaces in between, in the relational forces that connect and move the points. This symbol highlights those interconnections and de-emphasises the points. If you can see the relational forces connecting and moving the elements of a system, rather than focusing on the elements themselves, you are able to see a pattern outside of linear time. If you bring that pattern back into linear time, this can be called a prediction in today’s world.”

Aboriginal knowledge is relational and processual. The knowledge product itself is not as important as the communal knowledge process itself. In the Western world, however, Aboriginal knowledge is typically only considered as a resource. A resource that can be exploited and synthesised in Western knowledge systems. There is no interest in the process of aboriginal knowing.

The core of the book is a description of the five Aboriginal ways of knowing or minds. Kinship-mind is a way of preserving knowledge in relationships. Knowledge is stored in relationships and can best be retrieved if the relationship is reestablished. This way of knowing is not limited to social relationships.

“In our world nothing can be known or even exist unless it is in relation to other things. Most importantly, those things that are connected are less important than the forces of connection between them. We exist to form these relationships, which make up the energy that holds creation together. When knowledge is patterned within these forces of connection it is sustainable over deep time.”

Story-mind is about the role of narratives and songs in knowledge transmission and memorisation. Dreaming-mind is about the role of metaphors to work with knowledge. The connection between abstract and tangible knowledge. Ancestor-mind is about deep engagement with culture and land for learning. It is characterised by a state of complete concentration. Pattern-mind is about seeing systems as a whole and the trends and patterns within them. It is about truly holistic, contextual reasoning. Taken together, an Aboriginal orientation to research would examinine multiple interrelated variables situated in place and time rather than independent of context. It is about holistic reasoning which requires a lived cultural framework embedded in the landscape and the patterns of creation one follows there.

Yunkaporta argues that Aboriginal knowledge could provide a pathway for a more sustainable future. To design sustainable ways of living we need to pay attention to the processes through which systems came to be. Not only to the knowledge product. Solutions can only be designed from within a deep understanding of the system rather from the outside. Aboriginal culture defines four operating guidelines of sustainability agents. Connectedness balances the excesses of individualism in the diversity principle. Diversification compels to maintain individual differences. Interaction provides the energy and spirit of communication to power the system. Adaption allow yourself to be transformed through your interactions with other agents and the knowledge that passes through you from them.